- Home

- J. A. Konrath

Shot Girl Page 3

Shot Girl Read online

Page 3

Bcuz; six, the cops will eventually show up. If that’s part of your plan, okurrr. If it’s not, don’t make it easy for them to find you or stop you.

Seven, wear protection. If peeps be shooting back @ you, rock the Kevlar, yo.

Eight, don’t leave evidence. Fingerprints on empty cartridge casings come back to convict. Don’t touch nothing without gloves, don’t bleed on anything, don’t let no one see your face, don’t leave footprints.

Nine, don’t overstay your welcome. Persimmons was still trying to shoot his boss when 5-0 came in and dropped him with extreme prejudice. Bruh never even returned fire.

Where’s the fun in that?

Ten, make sure you have two escape strategies, in case one gets effed up. That means knowing the layout of the place you’re going to hit. It also makes it easier to maximize kill count.

Efficiency, bruh. Case the place. Learn the floorplan. Know all the hiding spots where the screaming losers are going to cower, hoping you pass them by.

Don’t pass no one by. You want the speed run high score, every point counts.

There’s an eleventh rule, but I don’t want to dish about it now. Maybe later.

So here’s how the start of my story really went down.

I set my alarm for two hours early, got up and packed up my clothes and laptop, took a bunch of food from the kitchen and put it in a garbage bag (no birthday cake, eff you Moms), grabbed the car keys, and left a note on the counter.

TODAY I’M 18, AN ADULT WHO CAN MAKE MY OWN DECISIONS.

I QUIT SCHOOL AND QUIT MY JOB.

I’LL TAKE THE CAR AS MY BIRTHDAY PRESENT.

I’LL CALL YOU IN A WEEK AND LET YOU KNOW WHERE I AM.

Then I restored my cell phone to factory specs, erasing everything, left it on top of the note, and bounced.

The ride was a POS white suburban Toyota Camry. The solo time my moms let me drive it was the one time I used it to pass my driver’s test.

I sat in the driver’s seat, had a wicked little fantasy about going back into the house and bashing her beeatch face in while she slept, decided not to risk it, and then drove away from my old life.

I didn’t want to use the car GPS in case it could be tracked, so I’d already printed out directions @ school.

The drive time from Oakdale, Ohio to Katydid, South Carolina would take about ten hours.

I had half a tank of gas, a bag of food, nineteen thousand seven hundred and thirty-eight dollars in my bank account, and three hundred and six dollars in my money belt.

The gun show happened in two days.

Time for my life to really begin.

#HellsYeah.

“Woman must not depend upon the protection of man, but must be taught to protect herself.”

SUSAN B. ANTHONY

“We do not need guns and bombs to bring peace, we need love and compassion.”

MOTHER TERESA

JACK

I cleaned up in my Mom’s room, borrowing a pair of her sweatpants, sticking my dirty clothes in a plastic bag for housekeeping to launder.

Mom was immune to my shame, phubbing me for YouTube dog tricks.

I wheeled downstairs to catch my ride.

My husband, Phineas Troutt, pulled in front of the Darling Center and I rolled up to our van as he got out and opened the side door and pulled out the chair ramp.

Wind tousled my hair, raising goosebumps on my bare arms. I still wasn’t used to the smell of Ft. Myers, especially when a storm was moving in. Salt water and seaweed and static electricity. So different from my home, Chicago.

But Chicago wasn’t my home anymore.

Phin gave me a kiss on the head. “How was work, dear?”

I didn’t tell him that it wasn’t really work, because I wasn’t getting paid for it. Ironic, to be volunteering at the same place we were paying out the ass for my physical therapy. We were whipping through our savings because we didn’t have insurance because we were living under fake names. I attracted dangerous maniacs like nectar attracts bees, and unlike Phin’s psychotic brother, Hugo, who was locked away in a Supermax prison, I still had killer stalkers leftover from my old police job who were out there somewhere, hunting me.

Long story.

I didn’t tell him that I pissed myself during rehab, just like I pissed myself a few months ago, all over the bed and all over him, the last time we had sex.

I didn’t tell him that my mother thought I was depressed and was forcing me to see a shrink.

I just said, “Fine. Where’s Sam?”

“Sleepover at Taylor’s house. Her mother called to make sure it was okay to watch Frozen because it’s rated PG.”

The last movie we watched with Sam was the uncut version of Aliens.

We were probably terrible parents.

Phin pushed me up the ramp, and I didn’t try to fight him; sometimes I insisted on getting into the van by myself. Today I was too tired. I locked my wheels in place and he closed the door and walked around me and plopped into the driver’s seat.

“Did you think this is how it would be?” I asked.

“What do you mean? Married to the greatest woman on the planet?”

I hated when Phin tried to cheer me up. My husband was a hard ass, and some of my favorite memories of us are when we had fist fights; actually full contact where we tried to knock each other out.

Sounds dysfunctional. With us, it was more like flirting.

But that was back when I could actually stand toe-to-toe with him. When we were equals.

Now we were a victim and a caregiver, and both of us sucked at it.

“Why the pissed-off face, Jack?”

Did he actually want to start an argument? I perked up.

“Have you noticed? I’m in a wheelchair.”

“It’s hard not to notice, because you bring it up all the time.”

Here we go. I’d been waiting for this. “What are you saying?”

“You’re letting it define you.”

“Says the guy who has been dying of cancer for how long? Like twenty years?”

“I’m in remission. And I never let it define me.”

I snorted at that. “Of course you let it define you. You used it as an excuse for all the shitty things you did.”

Phin didn’t reply. Which irritated me, because we both knew his checkered past was the only thing helping us get through our current financial crisis. Phin had hidden money from his criminal days. I pretended not to know about it, even though I found the hiding place in the garage when we moved to Florida.

One more thing we didn’t share.

If the key to a successful relationship was communication, our marriage would be over by the end of the week.

“Whatever you say, Jill.”

Jill was my fake Florida name. Phin was Gil. Jill because of Jack and Jill, and Gil because it was a part of a fish, like Phin.

“How about you answer my question, Gil?”

“Fine. I’ll answer your question. Did I think this was how it would be? No. I married an exciting, tough, funny, strong, smart woman who made me feel like I had a future.”

“And now that woman’s crippled, and you want out.”

“Wrong. Now that woman has given up, and I want to shake the shit out of her.”

“So do it, Gil. It would be better than you trying to sound like a goddamn Hallmark card all the time. You’re such an asshole.”

I wanted him to slam on the brakes and shake me. Or kiss me. Or both.

Anything other than the tsunami of pity and fake cheer and relentless encouragement that had invaded our marriage.

But instead Phin turned on the radio.

“…Harry is hammering the shore of Tobago with three-foot swells, and all coastal residents are being evacuated as the winds reach upwards of one hundred and thirty miles per hour.”

“I don’t want to listen to the radio.”

Phin turned it off rather than fight about it. Asshole.

We drove

for a while in silence. When he turned down the street we lived on, I felt myself bridle.

“I don’t want to go home.”

The idea of Phin and I spending a night without Sam, pretending to be happy, was too much to deal with.

“Dinner?”

“Not hungry.”

“Movie?”

“Nothing good is playing.”

I had no idea if that was true or not. I hated watching movies in my wheelchair. Everyone else had reclining theater seats, and I was crippled and uncomfortable and aware of it every single second of the running time.

“Want me to drive around Sarasota randomly until you figure out what it is you want?”

“I want to get drunk.”

He seemed to consider it and then said, “I know a place.”

I’m a Chicago girl, so I’m spoiled on good places to eat and drink. Florida didn’t lack for decent restaurants, especially seafood. But bars were a different animal. In my home town, we had taverns where adults could hang out without dealing with crowds, college kids, or tourists. Especially tourists. Real gin joints, with good beers and honest pours.

I hadn’t found a suitable substitute in the Gulf area yet.

How did Phin find one?

After my injury, I’d begun taking sleeping pills. Insomnia and I have always been dance partners, but it took the lead after I got shot. Physical pain, mental pain, emotional pain, existential pain; I’d never sleep again without Zolpidem. On the plus side, it knocked me out and didn’t give me a grogginess hangover. On the minus side, it was a memory eraser. I couldn’t remember anything about ten minutes after taking my nightly dose, and the next morning I didn’t even remember falling asleep.

And sleep was an unawakenable coma.

Could Phin have been sneaking out at night while I was knocked out? Prowling local bars? Looking to get laid, because he wasn’t getting it at home?

Would Phin do that?

I had no clue. A year ago, I would have said no way. Phin is loyal like our dog, Duffy, is loyal. And he’d never leave Sam alone with me after I took a pill.

But ugly doubts crawled into my skull and twitched.

I stared at him in the rearview mirror, and he saw me looking and grinned.

Was he a lying asshole?

Or was I the asshole?

I’d been dealing with some jealousy issues prior to getting shot. Phin hadn’t done anything to prompt my insecurity. Some of it was circumstantial; leaving my job, changing our identities, becoming a mother, getting older. My husband was younger, fitter, more attractive. He didn’t have gray hair or crow’s feet or stretch marks. I don’t want to get into ageism or body shaming or a culture that worships youth and beauty and disregards women over fifty. But the billion-dollar cosmetic industry was doing well, and even though high heels are the stupidest invention ever I still own over a hundred pairs, even though I’ll likely never walk again in anything taller than a flip-flop.

Does Givenchy make anything with Velcro laces?

So my self-esteem circled the shitter prior to my partial paralyzation. Add ten months of being a whiney, self-loathing burden, and I wouldn’t blame Phin for finding something on the side.

To show how far into a hole I’d fallen, Phin sleeping with other people wasn’t even the thing that bothered me. Neither was the deceit that came along hand-in-hand.

What really freaked me out is that he might leave me for someone better.

He could lie. He could cheat. I could deal.

But I’d die if he left me.

Add abandonment issues to the neurosis pile.

Phin pulled into a parking lot, which was about half full, mostly with older model American cars and pick-up trucks.

I squinted at the glowing sign on the building.

COWLICK’S.

The W didn’t light up.

“Is this a cowboy bar?”

“I don’t know. Never been here.”

“How’d you find it?”

“Yelp.”

I felt a twinge of worry, and couldn’t tell if it was my old cop instincts saying “don’t go into a unfamiliar shitkicker bar” or my new insecurities saying “people are going to stare at you.”

Phin parked, then reached for my leg braces.

“No way.”

“They have a pool table. You need to stand for pool.”

I shook my head. “I don’t care. I hate those things.”

“They make you look like RoboCop.”

“They make me look like Forest Gump.”

“Only from the neck up.”

I searched Phin’s eyes. He was trying.

“If I have a few beers wearing those I’ll fall over.”

“What’s the worst that can happen? You hurt your back and become paralyzed?”

“You’re a dick.”

But I liked Phin busting my balls a lot more than I liked him pitying me. I guess I could meet him halfway.

I endured the indignity of Phin helping me into the braces, fitting them around my gym shoes, cinching them at the ankle, calf, knee, and thigh.

It irked me how much I liked Phin touching my thigh.

“Spring assist or not?”

The joints on the braces had three settings. Locked, which made them rigid, loose, which required me to keep my muscles flexed or else they’d bend, and spring assist, which was sort of halfway between the two, keeping some tension and giving me a bounce when I flexed.

“Spring assist.”

He adjusted the settings. “Chair or crutches?”

Ugh. I hated the forearm crutches more than the chair, but they’d give me more support while I stood. If we were actually going to attempt a game of pool, getting in and out of my wheelchair after every shot would exhaust me fast.

“Crutches.”

The front door had three stairs leading up to it.

What the hell? Wasn’t there a federal law about wheelchair accessibility?

Stairs were my nemesis. Even when I was in Full Metal Cripple mode. I couldn’t lift my body weight with my legs, and became overwhelmed with fear that I’d fall and hurt my spine again.

But rather than take my hand and help me balance, my husband scooped me up in his arms, leg braces and all.

He smelled good.

God, I missed him.

Phin set me down, propping me against the side of the van, gave me my crutches, and we began the awkward, painful, excruciatingly slow trip to the front door of Cowlick’s.

My husband walked alongside me, eyeing me the way he used to eye Sam when she’d graduated from crawling to toddling.

“Ready to catch me if I fall?”

“No. Ready to laugh at you and post the pics on Instagram.”

Good answer.

We eventually made it, and Phin held the door open for me, and I took a step inside and smelled the stale beer and heard the clackity-clack of pool balls and actually felt a tiny bit excited.

Then I had a closer look around and the excitement vanished.

As I’d hoped, it wasn’t a tourist bar where out-of-towners brought their kids after a long day mini golfing at Smuggler’s Cove, and it wasn’t a college spring break hangout where frat boys did tequila shots.

But, as I’d feared, it was a shitkicker bar. Drunk, loud locals, blowing off steam after a long week of middle-class work. My kind of people, if the vibe was right. But this vibe was off. Too many men, not enough women. Lots of wallets on chains. Lots of direct staring when I came in, with some snickers as guys exchanged jokes about the handicapped old lady.

Or maybe I was just being overly sensitive. I hadn’t been a cop for a long time. Maybe my cop-sense was malfunctioning.

“I’ll grab drinks,” Phin said, heading for the bar.

I lumbered to the empty pool table and tugged the triangle out of its hidey hole and placed it on the table; the universal symbol that we were playing next.

“Hey there little lady, that’s our table.”

I turned, found a guy standing way too close. Not just personal space close, but threatening to topple me over close. He had a handlebar mustache, wore jeans and an old Nirvana t-shirt, and I couldn’t tell if he was a redneck or a hipster. It didn’t matter, because I could tell he was a bully. His eyes were narrow and he smelled like whiskey and mean.

“You already have a table.” He was playing with an equally desirable specimen of manhood, this one in denim bibs, on the pool table to the left.

“Yeah, but my buddies are coming.”

“Sign on the wall says NO SAVING TABLES.”

“That sign don’t apply to me.”

And then something really strange happened.

I was afraid.

Fear and I went way back. I had so many life or death situations during my career that I couldn’t even remember them all.

But my fight-or-flight adrenaline response usually prompted action. It gave me a surge that sharpened my thoughts and supercharged my reflexes and slowed down time so I could make critical decisions fast, usually with beneficial results.

But standing there, staring at this bully, I didn’t act.

I froze.

I couldn’t move. Couldn’t talk. Couldn’t even breathe.

My brain went into overdrive, and I thought a dozen thoughts at once.

I can’t fight back. I’m crippled.

Where’s Phin?

I hate that I need Phin.

Why didn’t I take my wheelchair? I have a gun in my wheelchair.

What am I so scared of?

What if he hits me and I’m paralyzed forever?

What if he kills me?

Would that be so bad?

How could I be afraid of this stinky little drunk man?

I’ve fought monsters.

I’ve beaten monsters.

But I’m no longer that person.

“Is there a problem?”

Phin, coming up from behind. Two beers in one hand. Two shots in the other.

What Happened to Lori

What Happened to Lori Shot Girl

Shot Girl Street Music

Street Music Dead on My Feet

Dead on My Feet What Happened To Lori - The Complete Epic (The Konrath Dark Thriller Collective Book 9)

What Happened To Lori - The Complete Epic (The Konrath Dark Thriller Collective Book 9) Chaser

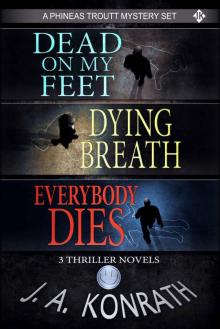

Chaser Dying Breath - A Thriller (Phineas Troutt Mysteries Book 2)

Dying Breath - A Thriller (Phineas Troutt Mysteries Book 2) Jack Daniels Six Pack

Jack Daniels Six Pack Jacked Up! (A Lt. Jack Daniels/Leah Ryan Mystery)

Jacked Up! (A Lt. Jack Daniels/Leah Ryan Mystery) Fuzzy Navel

Fuzzy Navel STOP A MURDER - WHERE (Mystery Puzzle Book 2)

STOP A MURDER - WHERE (Mystery Puzzle Book 2) Epitaph

Epitaph Hit: A Thriller (The Codename: Chandler)

Hit: A Thriller (The Codename: Chandler) Cheese Wrestling: A Lt. Jack Daniels/Chief Cole Clayton Thriller

Cheese Wrestling: A Lt. Jack Daniels/Chief Cole Clayton Thriller Shapeshifters Anonymous

Shapeshifters Anonymous STOP A MURDER - HOW (Mystery Puzzle Book 1)

STOP A MURDER - HOW (Mystery Puzzle Book 1) Bloody Mary

Bloody Mary Dying Breath

Dying Breath Everybody Dies - A Thriller (Phineas Troutt Mysteries Book 3)

Everybody Dies - A Thriller (Phineas Troutt Mysteries Book 3) DRACULAS (A Novel of Terror)

DRACULAS (A Novel of Terror) Shot of Tequila

Shot of Tequila Last Call - A Thriller (Jacqueline Jack Daniels Mysteries Book 10)

Last Call - A Thriller (Jacqueline Jack Daniels Mysteries Book 10) Holes in the Ground

Holes in the Ground![Shaken [JD 07] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/01/shaken_jd_07_preview.jpg) Shaken [JD 07]

Shaken [JD 07] Flee, Spree, Three (Codename: Chandler Trilogy - Three Complete Novels)

Flee, Spree, Three (Codename: Chandler Trilogy - Three Complete Novels) Draculas

Draculas Jack Daniels Stories

Jack Daniels Stories Wild Night is Calling

Wild Night is Calling Rusty Nail

Rusty Nail STOP A MURDER - WHEN (Mystery Puzzle Book 5)

STOP A MURDER - WHEN (Mystery Puzzle Book 5) Whiskey Sour

Whiskey Sour Phineas Troutt Series - Three Thriller Novels (Dead On My Feet #1, Dying Breath #2, Everybody Dies #3)

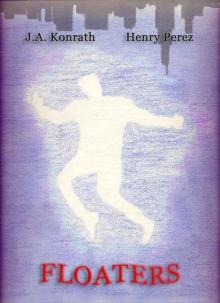

Phineas Troutt Series - Three Thriller Novels (Dead On My Feet #1, Dying Breath #2, Everybody Dies #3) Floaters - A Jack Daniels/Alex Chapa Mystery

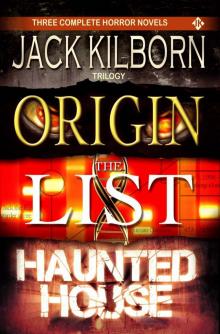

Floaters - A Jack Daniels/Alex Chapa Mystery J.A. Konrath / Jack Kilborn Trilogy - Three Scary Thriller Novels (Origin, The List, Haunted House)

J.A. Konrath / Jack Kilborn Trilogy - Three Scary Thriller Novels (Origin, The List, Haunted House)![Shaken (Jacqueline Jack Daniels Mysteries) [Plus Bonus Content] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/shaken_jacqueline_jack_daniels_mysteries_plus_bonus_content_preview.jpg) Shaken (Jacqueline Jack Daniels Mysteries) [Plus Bonus Content]

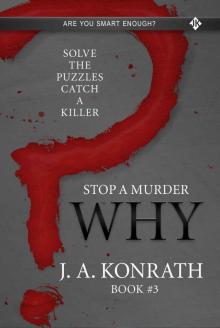

Shaken (Jacqueline Jack Daniels Mysteries) [Plus Bonus Content] STOP A MURDER - WHY (Mystery Puzzle Book 3)

STOP A MURDER - WHY (Mystery Puzzle Book 3) Dead On My Feet - A Thriller (Phineas Troutt Mysteries Book 1)

Dead On My Feet - A Thriller (Phineas Troutt Mysteries Book 1) Cherry Bomb

Cherry Bomb Rum Runner - A Thriller (Jacqueline Jack Daniels Mysteries Book 9)

Rum Runner - A Thriller (Jacqueline Jack Daniels Mysteries Book 9) With a Twist

With a Twist Dirty Martini

Dirty Martini Naughty

Naughty STOP A MURDER - WHO (Mystery Puzzle Book 4)

STOP A MURDER - WHO (Mystery Puzzle Book 4)